The hepatitis B virus is a DNA virus belonging to the Hepadnaviridae family causing hepatitis B in humans. Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver and can cause both acute and chronic disease.

Group: Group VII (dsDNA-RT)

Family: Hepadnaviridae

Genus: Orthohepadnavirus

Species: Hepatitis B virus

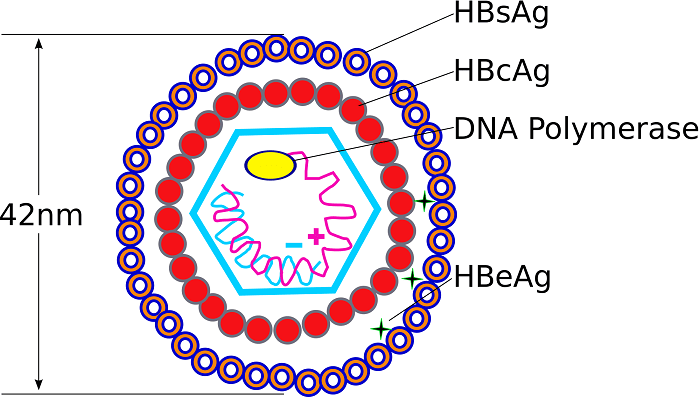

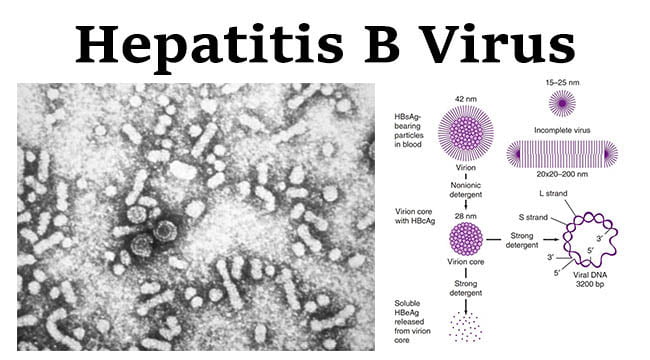

Structure of Hepatitis B Virus

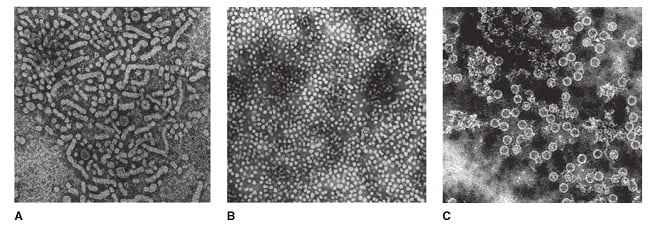

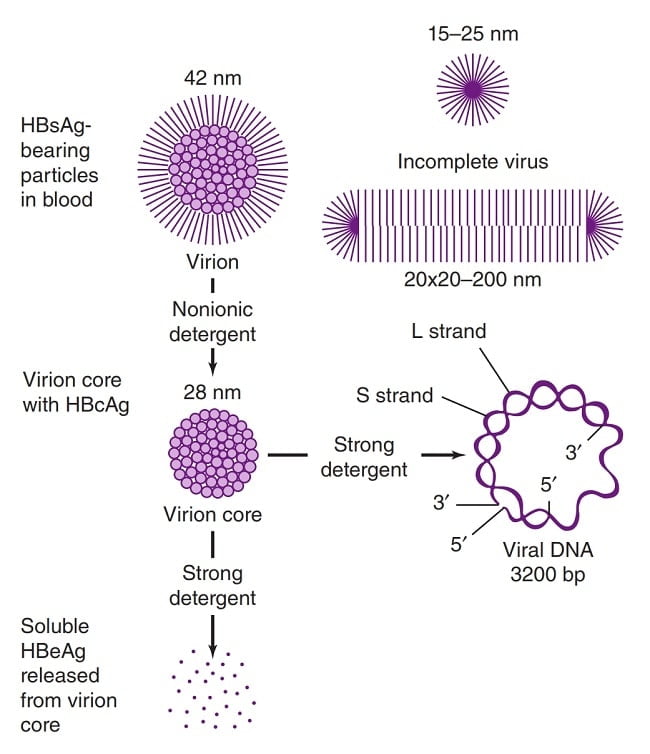

- Three types of viral particles are visualized in infectious serum by electron microscopy.

- 42 nm in diameter (Dane particle- Virion)

- 20 nm in diameter (Spherical Structures)

- 22 nm in diameter (Filamentous Particles)

- Contains icosahedral nucleocapsid, the core (27 nm) and outer envelope (4 nm)

- There is an outer shell (or envelope) composed of lipid and protein that is termed “surface antigen” or “HBsAg”.

- Inner protein shell that is referred to as the core particle or “HBcAg”, contains the viral DNA and enzymes used in viral replication (called “DNA polymerase”).

- HBeAg (hepatitis B e antigen) is the antigenic determinant that is closely associated with the nucleocapsid of HBV. It also circulates as a soluble protein in serum.

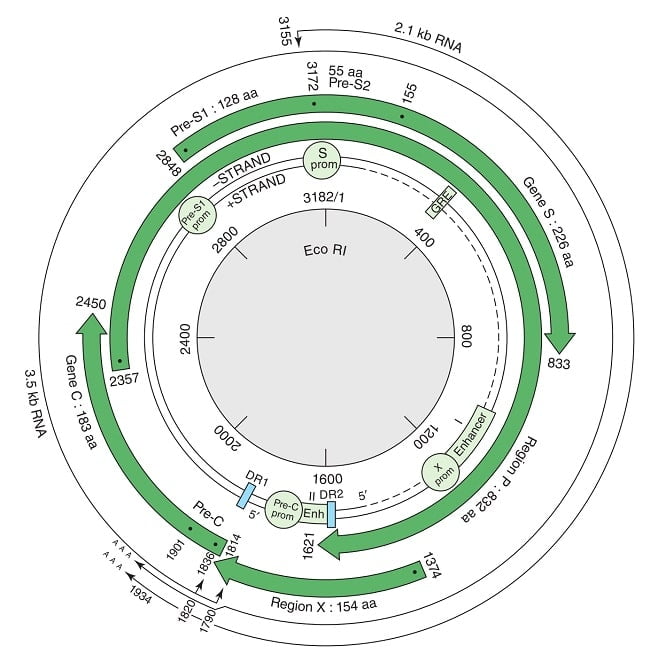

Genome of Hepatitis B Virus

- Genome is partially double-stranded DNA that forms a covalently closed circle with 5′ end of the full length minus strand which is linked to the viral DNA polymerase.

- Circular, non-segmented and approximately 3.2 kilobase (kb) in size.

- The genome is 3020–3320 nucleotides long (for the full length strand) and 1700–2800 nucleotides long (for the short length strand).

- Compact organization, with four overlapping reading frames running in one direction and no non-coding regions.

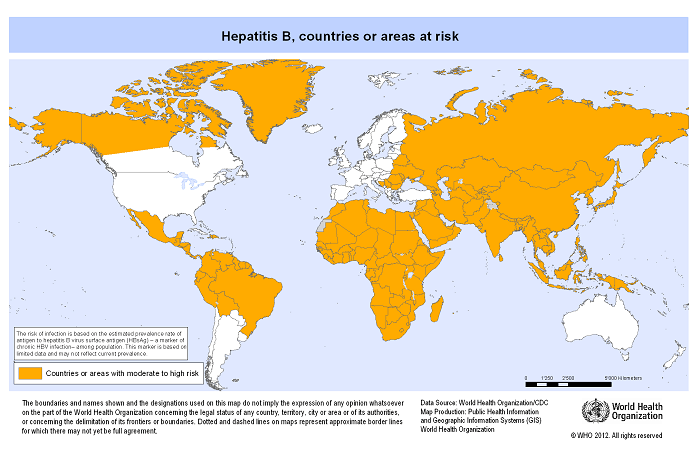

Epidemiology of Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis B prevalence is highest in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia, where between 5–10% of the adult population is chronically infected.

- Globally, 240 million people infected with hepatitis B and 786,000 people die every year due to complications of hepatitis B.

- In 2013, there were an estimated 19,764 new hepatitis B virus infection in the United States with an estimated 700,000 to 1.4 million persons having chronic hepatitis B virus infection.

Signs and Symptoms of Hepatitis B

Only 30% to 50% of adults develop significant symptoms during acute infection.

The incubation period of the hepatitis B virus is 75 days on average, but can vary from 30 to 180 days.

- Fever, a flu-like illness

- Fatigue

- Dark urine

- Loss of appetite

- Nause, Vomiting

- Joint pain

- Clay-colored bowel movements

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

- Pain in the upper right abdomen (due to the inflamed liver)

- People with chronic Hepatitis B develop serious liver conditions, such as cirrhosis (scarring of the liver) or liver cancer.

Transmission of Hepatitis B

- Transmitted through blood and infected bodily fluids as well as through saliva, menstrual, vaginal, and seminal fluids.

- Transmit through direct blood-to-blood contact, unprotected sex, use of unsterile needles, and from an infected woman to her newborn during the delivery process.

- Infection can occur during medical, surgical and dental procedures, tattooing, or through the use of razors and similar objects that are contaminated with infected blood.

- Rarely, hepatitis B can be transmitted through transfused blood products, donated livers and other organs.

- Hepatitis B is not spread through food, water, or by casual contact.

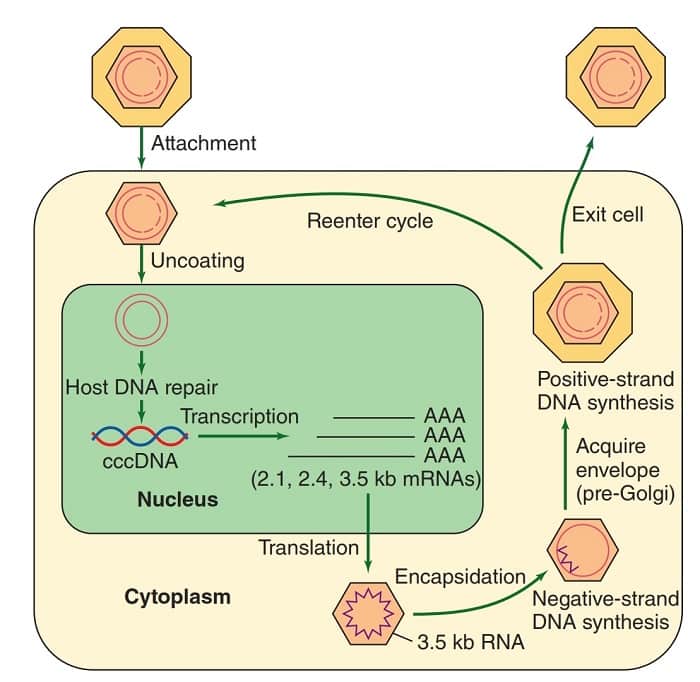

Replication of Hepatitis B Virus

- The infectious virion attaches to cells and becomes uncoated.

- In the nucleus, the partially double-stranded viral genome is converted to covalently closed circular doublestranded DNA (cccDNA).

- The cccDNA serves as template for all viral transcripts, including a 3.5-kb pregenome RNA.

- The pregenome RNA becomes encapsidated with newly synthesized HBcAg.

- Within the cores, the viral polymerase synthesizes by reverse transcription a negative-strand DNA copy.

- The polymerase starts to synthesize the positive DNA strand, but the process is not completed.

- Cores bud from the pre-Golgi membranes, acquiring HBsAg-containing envelopes, and may exit the cell.

- Alternatively, cores may be reimported into the nucleus and initiate another round of replication in the same cell.

Pathogenesis of Hepatitis B

- Three mechanisms seem to be involved in liver cell injury during HBV infections.

- The first is an HLA class I restricted cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) response directed at HBcAg/HBeAg on HBV-infected hepatocytes.

- A second possible mechanism is a direct cytopathic effect of HBcAg expression in infected hepatocytes.

- A third possible mechanism is high-level expression and inefficient secretion of HBsAg.

- In the acute stage there are signs of inflammation in the portal tracts; the infiltrate is mainly lymphocytic. In the liver parenchyma, infected hepatocytes show ballooning and form acidophilic (Councilman) bodies as they die.

- In chronic hepatitis, damage extends out from the portal tracts, giving a piecemeal necrosis appearance. Some lobular inflammation is also seen. As the disease progresses, fibrosis and, eventually, cirrhosis develops.

- Chronic liver damage results from continuing, immune-mediated destruction of hepatocytes expressing viral antigens. In addition, autoimmune reactions may contribute to the damage as immune responses are induced to various liver-specific antigens.

Diagnosis of Hepatitis B

- The diagnosis of HBV infection and its associated disease is based on a constellation of clinical, biochemical, histological, and serologic findings.

- The laboratory can test for a wide range of HBV antigens and antibodies, using immnoassays based on enzyme reactivity (EIA) or chemiluminesence (CLIA) and ELISA.

- HBV DNA can be quantified in serum or plasma using real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays.

- Focuses on the detection of the hepatitis B surface antigen HBsAg.

- Acute HBV infection is characterized by the presence of HBsAg and immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to the core antigen, HBcAg.

- During the initial phase of infection, patients are also seropositive for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). HBeAg is usually a marker of high levels of replication of the virus. The presence of HBeAg indicates that the blood and body fluids of the infected individual are highly contagious.

- Chronic infection is characterized by the persistence of HBsAg for at least 6 months (with or without concurrent HBeAg). Persistence of HBsAg is the principal marker of risk for developing chronic liver disease and liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) later in life.

Treatment of Hepatitis B

- The goal of treatment for chronic hepatitis B is to suppress HBV replication, prevent the progression of liver disease and thereby the development of cirrhosis, liver failure and HCC.

- Interferon alpha (α-IFN) is the first-line treatment option for patients without cirrhosis. Interferon has antiviral, anti-proliferative and immuno-modulatory effects.

- At a dose of 100 mg daily, lamivudine leads to a marked reduction or elimination of detectable HBV DNA in plasma in about 40% of HBeAg positive and 60–70% of HBeAg negative patients.

- Telbuvidine is a L-nucleoside analogue with potent anti-HBV activity. It is similar to lamivudine in mechanism of action and resistance profile but is more potent. However, its use is limited due to a high rate of resistance and cross-resistance with lamivudine.

- Emtricitabine is another L-nucleoside analogue with similar activity to that of lamivudine.

- Adefovir is a nucleotide analogue of deoxyadenosine monophosphate that has demonstrated efficacy in suppressing HBV DNA (20–50%) and normalizing liver function (50–70%).

- Entecavir is a carbocyclic analogue of 2′ deoxyguanosine. It is a potent suppressor of HBV replication, resulting in loss of serum HBV DNA in 70–90%, and ALT normalization in 70–80% of patients.

- Tenofovir is a nucleotide analogue initially approved for the treatment of HIV. It is often used in a coformulation with emtricitabine. After 48 weeks of therapy with tenofovir, HBV DNA loss is achieved in 80–90% and ALT normalization in 70–80% of patients.

- Orthotopic liver transplantation is a treatment for chronic hepatitis B end-stage liver damage. However, the risk of reinfection on the graft is at least 80% with HBV presumably from extrahepatic reservoirs in the body.

Vaccines of Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis B is a vaccine-preventable disease.

- A vaccine for hepatitis B has been available since 1982.

- The Hepatitis B vaccine is safe and effective and is usually given as 3-4 shots over a 6-month period.

- Plasma-derived vaccines: The initial vaccine was prepared by purifying HBsAg associated with the 22-nm particles from healthy HBsAg-positive carriers and treating the particles with virus-inactivating agents (formalin, urea, heat).

- Recombinant DNA-derived vaccines: These vaccines consist of HBsAg produced by a recombinant DNA in yeast cells or in continuous mammalian cell lines. The HBsAg expressed in yeast forms particles 15–30 nm in diameter, with the morphologic characteristics of free surface antigen in plasma, although the polypeptide antigen produced by recombinant yeast is not glycosylated. The vaccine formulated using this purified material has a potency similar to that of vaccine made from plasma-derived antigen.

- The HBsAg vaccines (HB) can be combined with other vaccines such as Calmette-Guérin bacillus (BCG), measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), Haemophilus influenzae b (Hib), and diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis combined with polio (DTP-polio).

Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B

- The hepatitis B vaccine is the mainstay of hepatitis B prevention.

- WHO recommends that all infants receive the hepatitis B vaccine as soon as possible after birth, preferably within 24 hours.

- Simple environmental procedures can limit the risk of infection to health care workers, laboratory personnel, and others. Examples of specific precautions include the following:

- Gloves should be used when handling all potentially infectious materials;

- protective garments should be worn and removed before leaving the work area;

- masks and eye protection should be worn whenever splashes or droplets from infectious material pose a risk;

- only disposable needles should be used;

- needles should be discarded directly into special containers without re-sheathing;

- work surfaces should be decontaminated using a bleach solution; and laboratory personnel should refrain from mouth pipetting, eating, drinking, and smoking in the work area.

- Metal objects and instruments can be disinfected by autoclaving or by exposure to ethylene oxide gas.

References

- Kenyon College. Biology 238: Microbiology. Dr. Joan Slonczewski. What is HBV?

- Microbe Wiki. Hepatitis B virus.

- Viral Hepatitis – Hepatitis B Information

- Vaccines and Immunizations. Hepatitis B. The Pink Book: Course Textbook – 13th Edition (2015)

- Media Center. Hepatitis B

- Emergencies Preparedness, Response. Hepatitis B. The hepatitis B Virus

- Hepatitis B Foundation. Hepatitis B Virus

- Medicine Net, Inc. Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis Health Center.

- Christoph Seeger and William S. Mason. Hepatitis B Virus Biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. March 2000 vol. 64 no. 1 51-68.

- Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: The Virus and Disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2009;49(5 Suppl):S13-S21. doi:10.1002/hep.22881.

- Upto Date: Epidemiology, transmission, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection.

- Zuckerman AJ. Hepatitis Viruses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Chapter 70.

- Jawetz, Melnick & Adelbergs. Medical Microbiology 27 E (Lange)

- David Greenwood, Richard C. B. Slack, Michael R. Barer, Will L Irving. Medical Microbiology, 18e.

- Wong’s Virology. Hepatitis B.

Sir my son is a healthy carrier of hepa v virus this is the reason why he cant pursue his dreams to work abroad everytime he undergo medical exam local physician would always say he is fit to work but the problem foriegn doctors esp. in dubai will not accept this kind of findings Is their anything you can do to help me

This write up is highly Technical( Medically).. Although symptoms have been written, what is more IMPORTANT for “layman” like us is to show what need & MUST be done to prevent Hepa(B).. This article therefore need to be published in two parts..(1) Technical( Medically) and (2) Language of the “layman” ,

Thx